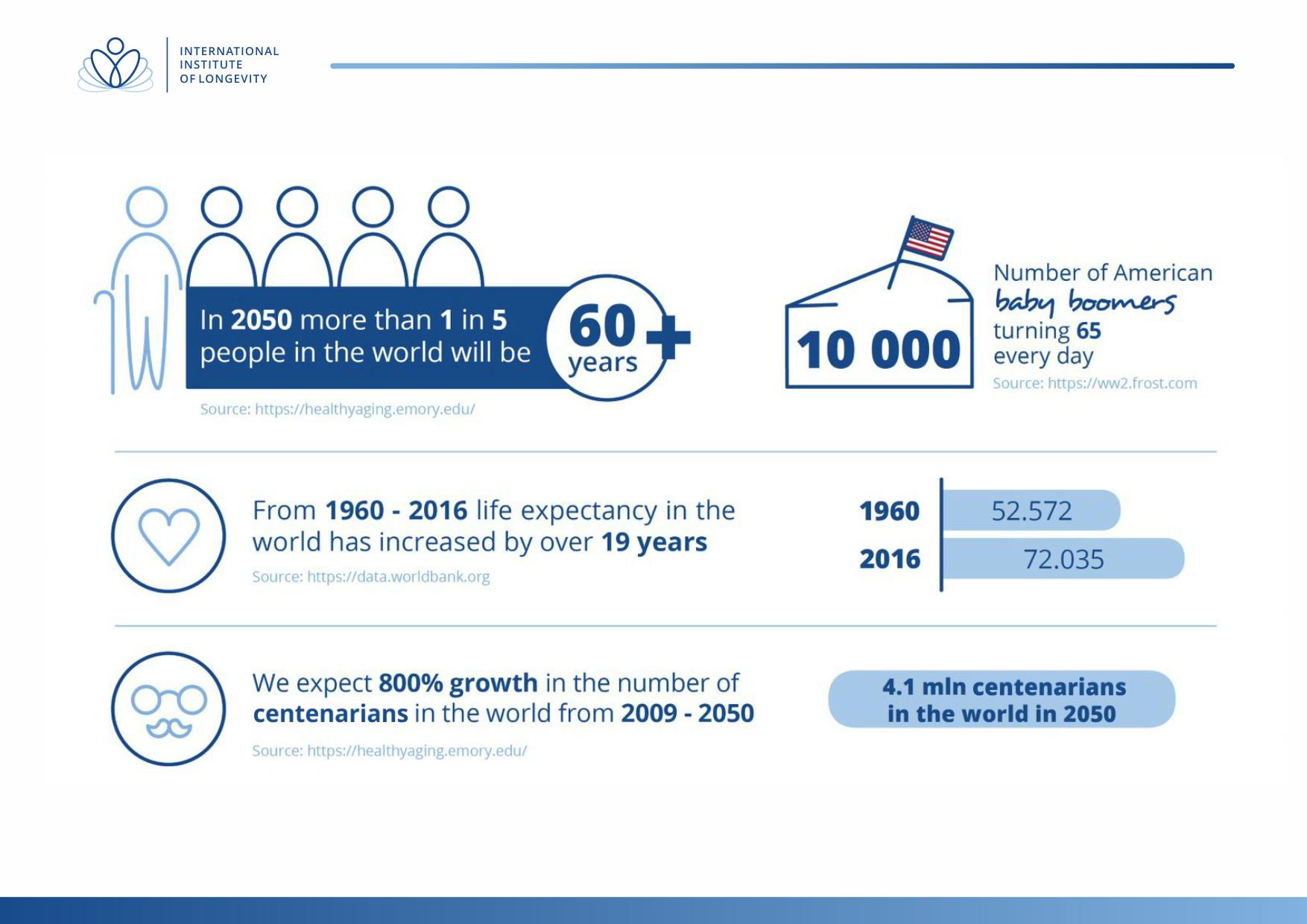

By 2050, it’s estimated that 20 percent of the world’s population will be over 60 with 4 million of those over a 100. This will inevitably impact budgetary policies, pension funds and healthcare systems. In your opinion, how can we best prepare for this demographic change?

E. Rogers: Here at the Global Healthspan Policy Institute, headquartered in Washington, DC, we’re mostly focused on the health span, which is the period that people are healthy before they die. So if you focus on the health span, you can increase productivity, and lower the cost of chronic diseases, which is a huge problem in the United States and also around the world. We are looking for ways to treat the underlying condition of chronic diseases, which usually by around 5,000 percentage points, is the process of aging, whether it be cancer, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, dementia, Alzheimer’s, or arthritis, the main cause of which is the aging process. By 2030, U.S. adults, age 65 and older, will more than double to 71 million and this pattern is reflected in most of the advanced developed countries.

And that’s only 11 years from now. So it’s not even a half a generation away.

E. Rogers: Yes. Above the age of 65, which is generally our retirement age in the U.S. So that has a big impact on our Medicare spending, which is the health program for elderly people aged 65 and over and sponsored and paid for by the government, although people pay in throughout their work years. It’s estimated that the increase is going to be 25 percent and the cost will be about $9 billion. Currently, one-third of all Medicare spending, about $15,000 per person, is tied to age-related diseases. We’re looking at the possible valuable economic impact. If we are able to treat the underlying causes of aging, then the related diseases in the U.S. alone would project a saving of about $7.1 trillion over the next 50 years. Because of those numbers, we are able to start to get the attention of decision makers in the U.S. When we hold meetings in the UK, we have the UK numbers, and German figures in Germany. They all look very similar. And so that causes people to ask, why don’t we spend some money, effort and time on the aging process and not just put it into treating cancer and heart disease?

Would you qualify the aging process as the most critical current issue to address? Could you also elaborate on what you mean by the aging process?

E. Rogers: We have experts at a lot of universities around the globe who talk about what exactly aging is, and that it is something that can be controlled and manipulated. And I’ve been in meetings with high-level experts in the U.S. government in the Medicare program, and they’ll say, aging is just a natural process, and there isn’t anything we can do about it. But that isn’t true at all. It can be manipulated, managed, controlled, and have good results. Like for example, I think people generally know that if you have a better diet and exercise, you are more likely to have better health outcomes, live longer and have a healthier life. In addition to diet and exercise, there are pharmaceuticals, treatments, supplements like vitamin D, drugs like metformin that are proven ways to slow down and treat the aging, the underlying cellular process of aging.

By 2030, U.S. adults, age 65 and older, will more than double to 71 million and this pattern is reflected in most of the advanced developed countries.

Where do you see the most interesting opportunities and challenges in aging?

E. Rogers: I would say that the biggest opportunity lies in measuring aging. If you can’t measure it, you can’t treat it and show results. People want to see a baseline. This is the best way to get individuals involved. With biometrics, for example, we can check your a1c, which is your glucose level, for the last three months. If it’s borderline diabetes, we know that has a big impact on longevity and particularly, the health span (the time that people are productive and healthy, before they start to get debilitating chronic diseases). We also know that if you can keep your a1c level low, you can keep your cholesterol level low, and your blood pressure in a certain range. Those are just three examples of biomarkers that are indicators of the aging process and there are many more, for example, vitamin D. Many people in the world have a shortage of vitamin D in their body and don’t even know it. Nor that it is essential for the life span of organs, muscles and bones. And that if you don’t die from a chronic disease, the odds are great that you’re going to die from a fall, so you do not want to become too fragile. We (in the scientific community) are all chasing the perfect set of biomarkers, and asking what they should be: 14, 24, 34, 500 or even 5,000 things? A lot of scientists have had meetings in the U.S., Italy, Asia, Russia, and around the globe, discussing exactly what those biomarkers should be, which ones are the most important ones. Because we can’t really wrap our mind in our pocketbook around hundreds of them.

Is it hard to find a correlation between too many metrics, too many biomarkers?

E. Rogers: So that’s exactly it. There are conversations that are taking place between organizations like the Global Healthspan Policy Institute and the Longevity Institute in Europe, where we, as a global charity, are facilitators. We create a platform where technology groups, patient advocacy groups, governments, universities and scientists can come together and have the opportunity to put together white papers on what is the most important thing that we need right now, such as biomarkers. Then, after we get a set of biomarkers in place that we can all agree on, what would be the process to keep them up-to-date and disseminate them, and what would be the best practices to treat and manage those biomarkers to get them in an acceptable range so that we do not do things without realizing that increase our chances of an early demise?

I spend a lot of time talking to laboratory researchers about what they have discovered. Then we prepare a translational science piece so that the policymakers and government officials can understand what’s happening. Scientists have told me that they are pretty sure they have a cure for juvenile diabetes but don’t know what to do with it. They are onto the next paper in another field and don’t know how to get this information out. So another thing that we focus on is disseminating that information, making it available to the public, especially getting it to other researchers, so they can use it in their research and their conclusions. We’re like honey bees pollinating different groups by trading information around at no cost and for the common good.

Does your institute also serve an educational role to the governing bodies?

E. Rogers: It is near impossible to create a worldwide consumer campaign so the way we work is in coalition with the major stakeholders such as researchers, universities, pharmaceutical companies, patient advocacy groups, consumer advocacy groups and governments. We create a platform where they can talk and share information, and then develop pilot projects. The next step is to go to major world employers that have populations of anywhere from 300,000 to a million employees and you implement test projects. You can also do it through government healthcare programs, where biomarkers are used in treatment programs to target underlying aging process. That’s the best way to disseminate information and solutions through the coalition process that we’re involved in, and spearheading, with similar groups to the Global Healthspan and Policy Institute.

I spend a lot of time talking to laboratory researchers about what they have discovered. Then we prepare a translational science piece so that the policymakers and government officials can understand what’s happening.

This is also a major area of interest for international corporations at a time when companies are looking at ways to keep their employees happy and healthy.

E. Rogers: That’s right, we have to prepare publications constantly. The process would be to go to a large company such as Facebook and Google. They are in the business of employee retention, keeping their employees healthy and happy at work, at home. So they are always looking at ways to increase their health span, and prevent chronic diseases. So the best way to do that is not, as we talked about earlier, not targeting the diseases one by one, (there are approximately 14 chronic diseases that are caused mainly by aging), but to target the aging process itself. They can have programs for their employees where when they are having their annual physical checkup, they’re tested for these age-related markers. If a couple are bad or out of the norm, they can focus on getting those lowered through their primary care provider. Then there are employee tools and apps such as Inside Tracker and Inner Age which are being promoted to U.S. Fortune 500 companies, athletes and high-performance people. It is just starting to get down to the average population in the U.S. They have the basic aging markers in their profile and are working to expand it, and there are other companies. These are kind of pilot cases. Then we take those to state governments and federal governments around the world, and show them that it doesn’t work unless you show them better outcomes for the employee or the population. You also have to show healthcare savings usually, within some time period, it can’t be 10, 40 or 50 years but has to be between 18 months and about three years.

Are there any proven treatments to reverse aging?

E. Rogers: When we talk to longevity experts, the general consensus is that with the information that we have available now, the average human could extend their life span by about six years on average, by doing what is currently available on the treatment side for aging. In the U.S., we just got approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the very first age-related drug to treat aging as a disease itself. This is very important because the FDA has never considered, nor have they ever approved, a drug for clinical trial to attack the aging process itself and treat it. They don’t have a formal list of diseases so we use the World Health Organization’s ICD 10 or ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases) but aging does not appear on that list.

The drug is called metformin, which is commonly available around the world and is a generic, and has very mild side effects. It’s been used for more than 60 years, I will say in Britain, in France, I think in the 1930s from French lilacs. And it has been proven to slow the aging process down and slow down the onset of a third disease if you already have two.

There’s plenty of research coming in from all over: Russia, the UK, the U.S., about the benefits of metformin. We can see clearly in the U.S. that if you’re someone with a borderline a1c and you are pre-diabetes, that if you take metformin, you’re less likely to get diabetes. And if you don’t have pre-diabetes, then you’re less likely to get the condition. It’s also been proven to prevent a range of cancers and to slightly slow down the underlying aging process.

It’s much harder to get metformin utility or a prescription in most countries although there are some where you do not need a prescription. It is generally prescribed for people with pre-diabetes or diabetes, but is very effective for all age-related chronic diseases of which I mentioned there are about 14.

That’s what the clinical trial in the U.S. is set to prove – it’s a six-year trial, costs $64 million, but it is hard to find the funding for it because it is such a generic drug, there’s no way for anyone to make money on it. So believe it or not, it’s hard to find the money for this clinical trial that will save governments trillions of dollars.

When we talk to longevity experts, the general consensus is that the average human could extend their life span by about six years on average, by doing what is currently available on the treatment side for aging.

What healthy habits have you introduced into your own life?

E. Rogers: I have access to a lot of information, and we have a task force that put together a database of exercise, pharmaceuticals and supplements, and diets that outperform a placebo. A Mediterranean diet turns up on top with all the research over and over. I can say that I have also implemented intermittent fasting. The process is to try to eat all your meals within an eight-hour period. Don’t eat over a 20-hour period, and then give your body only four hours to digest and restore. A lot of research has been done at the University of Southern California by Walter Lago, originally from Italy, on that particular concept. It is worth lowering the amount of protein that you’re consuming. It has been proven that the more protein you consume, the harder your body has to work to process it.

Dr. Lago and the longevity research people here in Southern California have shown that you only need around 30 grams of protein. Fifty grams and above taxes your body and shortens your life span. So keeping your protein just at the level that you need and not above is important. I found out that I was very low in vitamin D so I have a prescription for that. I have a Peloton bike so that I can get exercise daily or three, or four times a week. There’s plenty of research that shows that the right kind of exercise for just 10 minutes a day is all that you need and if you’re doing two hours, you don’t get any added benefit from that. I also have to admit that I take metformin.

Could you recommend a book that you’ve read in the past 12 months that really sparked your interest?

E. Rogers: Well, I’m a big picture person. So I would say when you think about aging, you think about longevity, the survival of humanity, and people who are debating and researching those topics. Just recently, I read Stephen Hawking’s last book that he wrote right before he passed away, called “Brief Answers to the Big Questions”. And he gets into a lot of the things that we’re talking about, at a 30,000-foot level. He talks about how do we shape the future, will artificial intelligence outsmart us, can we survive on our own, is there a god, how did every everything begin? I think the people who are comfortable with themselves, and their place in the whole multiverse, are more likely to be interested in their own survival, that of humanity, all other living beings and putting everything in perspective.